Subscribe to News Alerts

Ariel Sharon, proud Jew, decorated Israeli general, strategist and former prime minister of Israel, passed away Saturday at the Sheba Medical Center in Tel Hashomer, Israel. He was 85 years old.

Born in 1928 in Kfar Malal, in British Mandate Palestine, to Russian-born immigrants Shmuel and Devorah Scheinerman, Ariel—or “Arik,” as he was more commonly known—joined the Haganah, the precursor of the Israel Defense Forces, where he developed a name for himself as a brilliant field commander, strong leader and devoted soldier.

Sharon would eventually be considered the greatest field commander in Israel's history, with many also calling him the country's foremost military strategist. He lived life large, and his imprint and shadow upon his beloved country were large as well.

His strong-minded determination to do what he considered to be right for the Jewish people, regardless of conventional wisdom, earned him the nickname "the bulldozer" and many detractors who dogged him throughout his military career.

But to his friends he would speak about his concern for the Jewish people, not only in the immediate future, but, more importantly, “30 years from now and 300 years from now.”

After serving as a 20-year-old commander in Israel’s 1948 War of Independence, in which he was wounded in the battle for Jerusalem, he went on to play a central role in the formation and command of Unit 101, a special-forces unit that carried out many missions across Israel’s borders, which were consistently being infiltrated by terrorist bands from neighboring nations, particularly Egypt.

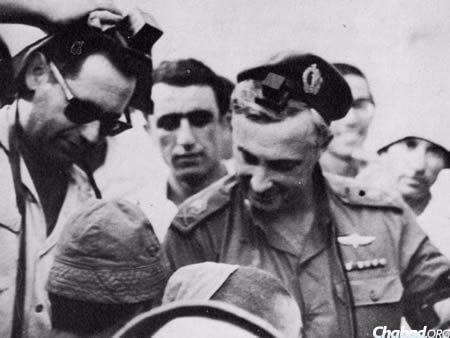

Sharon served as an officer in the 1956 "Suez War," and after a promotion to major general, he commanded a masterfully orchestrated attack on Egyptian troops in the Sinai Desert in the Six-Day War of 1967, playing a crucial role in Israel’s stunning six-day victory.

After the war, accompanied by his family and an entourage of high-ranking IDF and foreign military leaders, he visited the newly liberated Kotel (”Western Wall”) in Jerusalem, which had been in Jordanian hands for 19 years. Moved and inspired by what he recognized was a miraculous victory, Sharon expressed his gratitude by putting on tefillin at the nascent Chabad tefillin stand at the Kotel, while reciting the Shema Yisrael prayer proclaiming G‑d’s oneness. Media photographers captured the event, and it was subsequently circulated worldwide, giving a powerful voice to recognition of the divine intervention experienced in the Six-Day War.

Tragically, just a few weeks after the war, Sharon’s son, Gur, was killed by a fatal shot from a gun he and some friends had been playing with at home. He passed away in his father’s arms.

During the week of shiva, the Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory, dispatched a group of emissaries to pay the Sharons a condolence call.

The Rebbe also penned a long and heartfelt condolence letter expressing particular anguish over the painful irony that the tragedy had occurred under peaceful circumstances to someone who had merited to help secure the victory of the Jewish people just a short time earlier in war. In his memoirs, Sharon would recall the Rebbe’s letter to him as “warm and moving.”

Meeting the Rebbe

Less than a year later, in 1968, Sharon met the Rebbe face to face at 770 Eastern Parkway in Brooklyn, N.Y., the first of a number of lengthy private audiences Sharon had with the Rebbe. The Rebbe reviewed with the acknowledged military expert the latter’s battle strategy, asking him detailed questions about why he hadn’t followed a particular route to a certain city instead of going through a particular wadi, or why not use this piece of artillery that has these specific advantages over another that had been used, and other similar queries.

Later, Sharon said he had not expected to encounter in a Chassidic Rebbe a brilliant military strategist. He would recall that the Rebbe’s “incredible knowledge he exhibited in global affairs left an especially strong impression” on him.

In those heady days after the Six-Day War—when Israel seemed invincible and was respected the world over—the Rebbe nevertheless spoke with Sharon with great pain about the weakness and self-doubt the Israeli government was demonstrating in their international relations, as well as with their actions, which he said spoke even louder than words and would cause the gains in international relations to spiral downward.

The Rebbe was particularly pained that Israel did not state categorically that the liberated territories were now part of Israel proper, explaining that doing so unequivocally would gain the world’s respect and minimize bloodshed on both sides. The Rebbe urged Sharon, as he did others, to encourage the political leadership to stand strong for Israel’s security and not leave the situation in limbo.

The Rebbe also spoke with Sharon at length about the responsibility he and other Israeli leaders have to encourage Jewish education and Jewish practice worldwide, as the nationalist spirit alone could not sustain the Jewish people. Sharon later said he was astonished when the Rebbe told him with absolute certitude in that 1968 audience that the Iron Curtain would one day fall, and that the Soviet Jews would be free to leave.

It is clear from his writings and public talks that Sharon saw in the Rebbe the quintessential Jewish leader, one with whom he could speak openly about military strategy, political issues and existential matters important to the Jewish people as whole. In the Rebbe, Sharon saw a wise and sagacious guide, who would have an impact on his own spiritual life as well.

Years later, after the Rebbe’s passing in 1994, Sharon would reflect how he had been “distinctly privileged to meet with, and get to know up close, a one-of-a-kind sage in the wisdom of Israel, but also a far-seeing strategist, whose focus was on guaranteeing the continued existence and security of the Jewish people, wherever they may find themselves.”

The Rebbe Gives Military Advice

As his leadership in the IDF continued, Sharon continued to correspond with the Rebbe. At one point, the Rebbe expressed to Sharon his grave concern that the Bar Lev defense line in the Sinai Desert would prove insufficient in the face of a renewed attack from the Egyptians. The Rebbe compared it to the ill-fated French Maginot line, which proved disastrously ineffective in preventing German invasion in the spring of 1940. It later became known that Sharon, too, had shared these worries.

In what turned out to be pivotal advice, when Sharon sought the Rebbe’s counsel in 1970 about whether he should retire from the military and enter politics, the Rebbe strongly encouraged him to remain at his post.

“Your proper place is in the IDF, and it is there that with G‑d’s assistance you are successful and will continue to be so,” the Rebbe wrote Sharon.

The Rebbe went on to explain that his position is particularly strong about this because “the [political] path being followed is one that leads directly to renewed war, G‑d forbid, but in conditions far, far worse than they were [previously].” Sharon’s military service was therefore necessary for the protection of “the entire Jewish people residing in Israel.” Thus, the Rebbe said emphatically, “you must absolutely and certainly continue to serve in this very important capacity and role.”

Sharon heeded the Rebbe’s advice, but in early 1973 he was forced to leave the military as part of a national policy to retire many senior officers. He helped to negotiate the formation of a Likud (unity) front headed by opposition leader Menachem Begin. However, within a matter of weeks, the Yom Kippur War broke out, and Sharon was urgently called up to the war front.

In the first hours of the war, the Rebbe’s strategic analysis about the Bar Lev line was tragically proven correct when Egyptian forces overran it, costing hundreds of lives and contributing to the urgent panic felt throughout the country.

Yet despite the dim prognosis in the first days of the war, and the panic that had set in among some of the military and political leadership, the Rebbe insisted that Israel would still miraculously emerge victorious. Eventually, Sharon—who due to the additional years he spent in the military was able to seamlessly pick up the reins where he had left off—led an Israeli unit across the Suez Canal into Egypt, using his strategic expertise and leadership of his troops to encircle the Egyptian Third Army, nearly making it to Cairo. Sharon was hailed universally as the hero who reversed the course of the war.

A Deeply Personal Connection

Sharon’s growing connection to the Rebbe and Chabad was also deeply personal. He was a frequent visitor of Kfar Chabad, where he would come to celebrate Jewish holidays—and even celebrated the bar mitzvahs of his sons there.

In the ensuing decades, Sharon continued to travel to the Rebbe to receive his guidance and blessing. The Rebbe would urge him to do everything in his power to maintain Israel’s security, as well as promote Jewish engagement, education and mitzvah observance, which the Rebbe explained was crucial to Jewish continuity.

Sharon would come to say that this endeavor is “the primary means to guarantee Jewish continuity” both in Israel and the Diaspora. He would also comment how moved he was to see that wherever in the world he went, the Rebbe’s ideals about Jewish education and observance were being implemented.

His connection to the Rebbe also profoundly influenced his own religious beliefs and observance. Although Sharon described himself as a non-religious Jew, the Rebbe encouraged him in his observance, and Sharon would occasionally lay tefillin, would regularly hear the Megillah on Purim and welcomed the matzah for Passover that he received from the Rebbe’s emissaries. Sharon noted that he would frequently study the Bible, and he would eventually use phrases like “G‑d willing” when expressing his hopes for the future, a rarity among his generation of Israeli politicians.

Ongoing Political Career

In 1977, Sharon was elected to the Israeli Knesset under the banner of his newly formed Shlomzion Party. Shortly thereafter, it merged with Menachem Begin’s Likud Party, which had gained leverage for the first time after a history of Labor Party administration, and Sharon was appointed minister of agriculture. He would go on to hold a number of cabinet positions over the next few years.

Long before Sharon began his political career, the Rebbe stressed to him the folly of not embracing the territories that Israel had gained in the Six-Day War in 1967, telling him that Israel needed to believe in its own strength. Sharon took heed of this position and worked tirelessly to support the endeavor to renew Jewish life in Judea, Samaria and Gaza.

Later, as minister of defense, Sharon directed Israel’s 1982 incursion into Lebanon. Unable to control the actions of the Lebanese Christian militias they were trying to support, Sharon was forced to resign after accusations that he had failed to prevent the massacre of Palestinians and Lebanese Shiites in the Sabra and Shatilla refugee camps in Beirut.

The Lebanon war cast a pallor over Israel, politically and socially.

Still, Sharon went on to fill a number of key cabinet positions over the next two decades.

With the collapse of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s, the floodgates opened and hundreds of thousands of Russian Jews came to Israel. Sharon, who was then Minister of Housing and Construction, was tasked with formidable challenge of absorbing them into Israeli society.

He would later recall that very first meeting with the Rebbe in 1968, when the Rebbe predicted that the Iron Curtain would one day fall and the Soviet Jews would be free to leave. “I remember thinking that what the Rebbe was saying sounded impossible,” Sharon said. “But evidently anything is possible, and the Rebbe was right as always.”

In the Lead Role

In 2001, Sharon was elected prime minister of Israel.

That same year in September, the Palestinians launched a second intifada—much more violent and prolonged than a previous one back in the early 1990s. Buses and restaurants were bombed, and tourism came to a standstill; Israel suffered for four years.

Sharon’s wife, Lily, passed in away in 2000.

In 2004, investigations were launched in Israel for bribery and violations of campaign finance laws involving Sharon and his sons.

Increasingly alone, in 2005, Sharon conceived and oversaw Israel’s unilateral disengagement from the Gaza Strip, reversing his own long-held devotion to supporting Jewish settlements there. Shortly thereafter, Sharon left Likud and founded his own new party, Kadima.

In the years since, many of the tragic repercussions Sharon warned would result from Israel relinquishing land have come to pass. The disengagement left many open wounds from which Israeli society is still recovering eight years later.

On Jan. 4, 2006, Sharon suffered a major stroke and was placed under an induced coma from which he never recovered. Unable to carry out his duties, he was succeeded by his deputy prime minister, Ehud Olmert, the former mayor of Jerusalem.

Sharon suffered kidney failure in recent weeks, followed by further deterioration of his condition, leading to multiple organ failure on Saturday. He passed away surrounded by family and close friends.

A state funeral was being organized by the Prime Minister’s office. Sharon’s body will reside in the Knesset Plaza in Jerusalem on Sunday, where the public is invited to pay their last respects. A memorial service will be held at the Knesset on Monday morning, and many current and former world leaders are expected to attend. The funeral procession will proceed from the Knesset to Sharon’s farm in the Negev, where he will be laid to rest.

Sharon was predeceased by his wife, Lily, and his son Gur. He is survived by sons Omri Sharon and Gilad Sharon. His first wife, Margalit, passed away in 1962.

While Ariel Sharon will be remembered as a brilliant and fearless general and military strategist, as well as a formidable politician, perhaps the following words of his own best sum up his life's goals: “Before and above all else, I am a Jew. My thinking is dominated by the Jews' future in 30 years, in 300 years and in 1,000 years. That is what preoccupies and interests me, first and foremost.”

Join the Discussion