A mikvah is a pool of water in which Jewish people immerse to affect purity. It is most commonly used by women when they conclude their period of niddah and by converts as they become Jewish.

In this article, we’ll explore the most common type of mikvahs in use today.

The word mikvah means “gathering” and refers to (rain)water that has gathered naturally. So that means you can’t use buckets or other receptacles to transport the water to the mikvah. Water gathered in such a manner is called mayim she’uvim, “drawn water,” and is invalid for mikvah use. Rather, the modern mikvah typically uses water that has been gathered on its roof and transported via specially designed pipes and troughs.

The minimum amount of water in a mikvah is 40 se’ah (approximately 726-750 liters, or approximately 191-200 gallons). This measurement was given by the sages since it’s just enough for a person to stand in and bend their knees so that their head is underwater.1 Contemporary mikvahs are usually built to contain twice that amount of rainwater.2

One final point: The mikvah itself can’t just be a large receptacle, so it must either be built into the ground or be an integral part of a structure. Receptacles, like bathtubs, pools or Jacuzzis, typically can’t serve as mikvahs.

A Mikvah Is Born

In theory, the best place to find your mikvah would be out in nature. Oceans, wells, and spring-fed rivers and lakes appear to be the easiest and best mikvahs to use. Not so fast, though. In most cases, it’s not possible to use these bodies of water as mikvahs due to lack of accessibility, safety concerns, inclement weather, modesty and privacy issues. And aside from these concerns, there are often halachic issues as well. (In cases of urgent need, consult an Orthodox rabbi to see if you can use a particular body of water.)

So to meet the needs of Jewish life, Jews have constructed mikvahs throughout the ages.

The Double Pool

So far we’ve learned that a mikvah needs to contain “natural” water that has been gathered naturally into an inground pool. But using a single pool isn’t ideal logistically or hygienically. When the water gets dirty and needs to be changed, you’d need to wait for more rain (or transport snow according to very specific guidelines), which simply isn’t practical, especially in regions where precipitation is scarce.

A more feasible approach involves constructing a mikvah that doesn’t rely on fresh rainwater for its everyday upkeep.

Here is how it works. A mikvah is constructed with multiple pools (typically two). These are known as borot. One bor serves as the immersion pool (bor hatevilah), which contains tap water that is changed regularly, while the other pool (bor geshamim) holds natural rainwater.

But one second! How does that solve the problem? How can the fact that one pool holds rainwater help the person immersing in the other pool?

The answer lies in an important law that states that when tap water comes into contact with the “natural water,” it receives its status.

How is this contact arranged?

There are three primary techniques: Hashakah (“kissing”), zeriah (“planting”), and bor al gabai bor (“a pool on top of a pool”). Let’s discuss each one, along with their respective pros and cons.

Before proceeding, note that what follows here is just a very broad outline of some of the most intricate laws. A kosher mikvah needs to be built under the supervision of an expert rabbi and continuously supervised to ensure that its kosher status is retained.

Hashakah (“Kissing”)

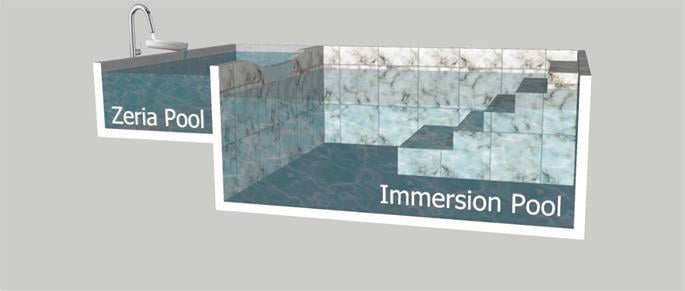

In this method, two pools (borot) are constructed side-by-side, with an opening between them. One pool (the bor hashakah) contains rainwater and the other (the bor hatevilah, immersion pool) contains tap water, and the waters “kiss” through an opening in the dividing wall.3

The opening must be at least the size of a shefoferet hanod (lit. “the mouth of a wine skin,” approximately the width of two fingers4). The hole should be higher than the level of 40 se'ah of rainwater in the bor hashakah (remember that the bor contains at least double the minimal 40 se’ah) and lower than the water level, so that the two waters actually come into contact.5

When the tap water is periodically replaced to maintain cleanliness, the new water “kisses” the rainwater through the hole and receives its status.

There are differences of opinion regarding placing a stopper in the hole. On the one hand, some prefer to use a stopper before emptying the mikvah in order to preserve the original rainwater, but on the flip side, forgetting to unplug the stopper after refilling the bor hatvilah renders immersions invalid, as the ordinary water doesn't touch the rainwater. Therefore, others prefer not to use a stopper, even though this results in losing some original rainwater.

Additionally, there is debate as to whether the hole must be open during immersion. Most contemporary mikvahs (including Chabad6) follow the approach that, ideally,7 it should be open during immersion.8 (Further elaboration on these points is beyond the scope of this article.)

Zeriah (“Planting”)

In the zeriah method, 40 se'ah of rainwater is collected in a reservoir. When needed, tap water is added (“planted”) to that reservoir. The tap water immediately becomes valid for immersion as it combines with the rainwater and takes on its status, just as a seed becomes part of the soil in which it is planted. The mixed water overflows through an outlet into the immersion pool.9

In a typical zeriah mikvah, two connected pools have a hole that is above the normal water level of both pools. When water is added to the bor zeriah, the water level rises to the hole and spills into the adjacent immersion pool. During immersion, the waters do not mix.10

This technique offers some advantages over the hashakah method: Tap water becomes kosher upon contact with rainwater. There's also no stopper involved. Once the bor zeriah is filled with rainwater, the mikvah is valid and reliable. The rabbi overseeing the mikvah doesn't need to worry about the connection between the mikvah waters and the bor or whether the stopper was removed. Another benefit is that the water in the bor zeriah changes frequently, remaining fresh.

On the flip side, the zeriah method has its own disadvantages.

For one thing, a mikvah lacking 40 se’ah of valid water is disqualified if it contains three log (a bit less than a quart) of invalid water. Thus, if the freshly cleaned immersion pool (which also must serve as the rainwater pool) had some “drawn” water leftover from the cleaning that had not been completely pumped out (which is quite common), the new water flowing in from the bor zeriah would be invalidated as soon as it entered the immersion pool and became one with the invalid water already there.11

Thus, a zeriah-based mikvah, without the additional presence of a hashakah pool, can be invalid, and there would be no way to remedy it without emptying it and starting again.

A second challenge to the zeriah method is that a mikvah is by definition a contained body of water, not one that flows or runs. A mikvah becomes invalid if its waters flow beyond its boundaries, such as leaking out through a hole or crack. Thus, some question how the zeriah pool can be effective if the water flows out of the bor zeriah during the process. (There are ways to get around this, but it is beyond the scope of this article.)12 13

Ebb and Flow

A disadvantage of both of these methods is natan se’ah venatal se’ah, which literally means “adding a se’ah [of tap water] and taking a se’ah [of rainwater].”

What happens if you keep adding and removing water from the mikvah? Eventually, there won’t be much of your original water in the pool. Is it still kosher?

According to most halachic opinions, it is.

However, the Raavad14 is of the opinion that once you have less than 20 se’ah (half) of the original rainwater present, the mikvah is invalid. And in both methods outlined above, it’s just a matter of time until the original water is diluted to the point that the mikvah no longer has 20 se’ah of rainwater.

Although on a basic halachic level, we don’t have to be concerned about this, there’s a well-accepted principle that we endeavor to build a mikvah to the highest standard.

So what’s to be done?

“The Chabad Mikvah”

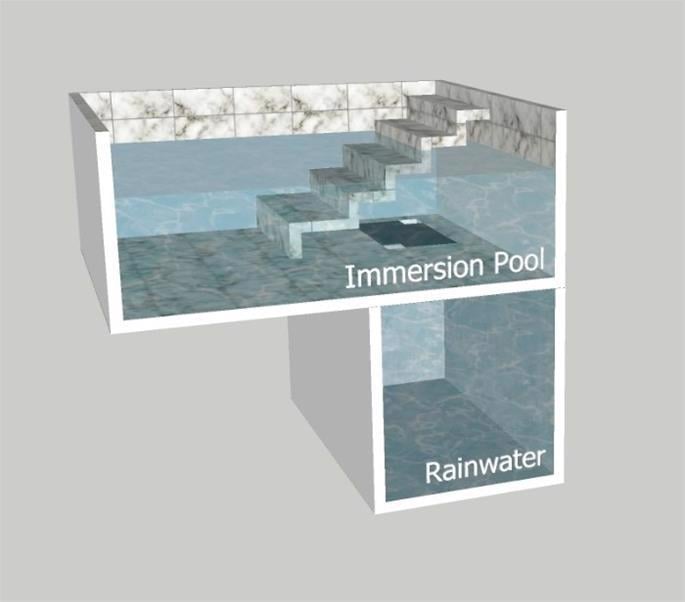

To resolve the potential issues outlined above, the Fifth Rebbe, Rabbi Shalom Dovber, of righteous memory, instructed that a mikvah be built using the bor al gabai bor method, which literally means "one bor on top of another bor." The construction process is as follows:15

First, a single deep bor is built.

Second, a cement divider is constructed, creating an upper chamber (for tap water) and a lower chamber (for rainwater). The divider serves as the floor for the upper bor and the ceiling for the lower bor.

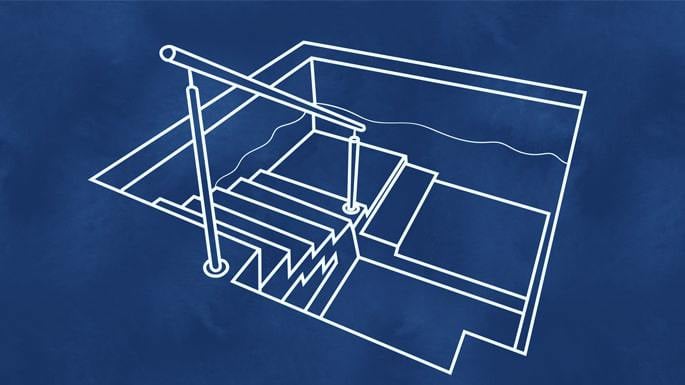

This mikvah is originally built with an opening in the divider, large enough for a person to pass through. It is later closed with a cover panel. Two holes, each measuring a square tefach (handbreadth), connect the chambers, allowing tap water in the upper bor to unite with the lower rainwater, validating the ordinary water for immersion.

Why two holes? Very simple. If something (such as the heel of a person immersing) plugs up one hole, the other hole still provides the connection. Thus, the holes are strategically placed so that one person cannot possibly stand on both at the same time.

When the mikvah is initially filled, rainwater is directed into the pool and drains down into the lower chamber, where it remains. The lower chamber is filled with 80 se’ah, twice the required amount, and should be filled to the top.

Then the upper chamber is filled with tap water. The tap water is made to run across an area of soft ground or cement, in a method known as hamshachah, which confers upon it a certain measure of “naturalness.” The water flows directly onto one of the holes, which also accomplishes the advantages of zeriah outlined above.

If the tap water doesn't flow directly over the holes, a different procedure is followed. First, the lower bor is filled with rainwater until it overflows, covering the floor of the upper bor. Then, ordinary water is added into the upper bor. Since the rainwater precedes the tap water, it qualifies as zeriah.

The mikvah is now valid and ready for use. When the water in the upper bor becomes dirty, pumping it out and refilling it is sufficient.

In contrast to the side-by-side hashakah technique, in this method there's no waiting for the waters in both borot to meet, and no need for a stopper. Once the lower bor is filled with rainwater, the mikvah is immediately valid and foolproof. The supervising rabbi can confidently ensure the mikvah's validity without concerns about the waters meeting at the hole or the attendant forgetting to remove the stopper.

This technique is similar to the zeriah method, where tap water flows directly into rainwater and is considered "sowed into the ground," with the advantage that the rainwater body is static rather than flowing.

This method also avoids the issue of eventually losing the original water. Since the rainwater bor is underneath the immersion pool, there is no significant flow of rainwater into the immersion pool even after repeated immersions. Additionally, since the immersion pool is warmer (as is almost always the case) and heat rises, there will be even less impact on the lower bor, and it will retain its requisite amount of water for a long time. Nevertheless, this does not take away the need to periodically check the mikvah and change the rainwater from time to time.

Another advantage is that both sections are considered one large bor. The presence of the square tefach hole(s) legally dismisses the divider. Therefore, when immersing in such a mikvah, one is essentially immersing in the rainwater itself.16

While we’ve given a brief overview of how mikvahs are constructed, the importance of constant supervision of a mikvah cannot be overstated. So be sure to only use a mikvah constructed and overseen by an expert rabbi.

Join the Discussion